Noah’s Land

Nakhichevan, also known as the ‘North Korea of Azerbaijan’, has long been characterised by surveillance and arbitrary arrests. But those who get involved with the region will find a place full of history, with breathtaking landscapes and people who live between hope and uncertainty.

With trembling hands, I pull the thin black gloves over my feet, already in two pairs of socks, hoping they will keep out the biting cold. The wind slams against the windows of the mountain hut, which sits at almost 2000 meters high in the remote village of Aghdara in Nakhchivan, an isolated region that is an exclave of Azerbaijan. The pale glow of my power bank dimly illuminates my room, which contains two metal beds from Soviet times. Above hangs a calendar from the year 2000, showing a woman in traditional dress smiling.

I lie back down on the worn-out mattress and cover myself with all available blankets and pillows. On the lower floor, Azerbaijani folk music blares from a small speaker – drums, a melancholic guitar, a woman's voice. Added to this is the snoring of my three companions. For the umpteenth time, I type "hypothermia" into my phone and check myself for symptoms like shivering and confusion. Eventually, I close my eyes.

Where on earth have I ended up?

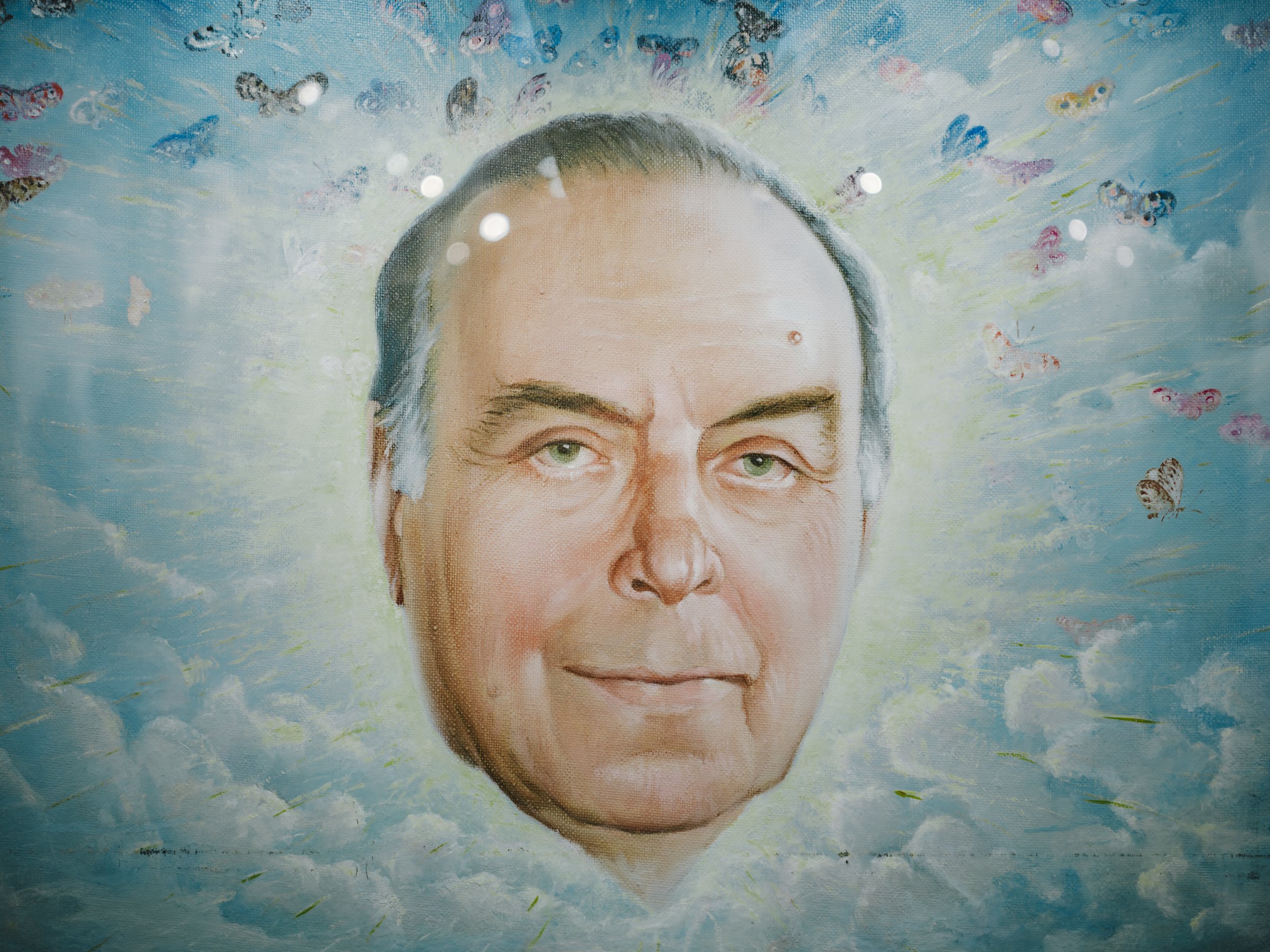

Vicken Cheterian, a lecturer in International Relations at the University of Geneva, has been researching the political conditions in the region for years. He explains that many members of Azerbaijan's political elite come from Nakhchivan, including the father of current President Ilham Aliyev. In December 1995, President Aliyev appointed a relative by marriage as president of the autonomous republic: Vasif Talibov.

During Vasif Talibov's decades-long rule, Nakhchivan earned the nickname "North Korea of Azerbaijan."

Talibov established a police state, had critics arrested and tortured. A 2010 report by the human rights organization Norwegian Helsinki Committee states: "The regime in Nakhchivan tries to prevent all signs of public discontent with the help of the police and suppress divergent opinions. Torture and mistreatment are widespread in prisons. The police officers enjoy de facto impunity. Instilling fear in the population is an important instrument to ensure obedience."

At the end of 2022, Talibov suddenly resigned, officially for "health reasons." Cheterian sees this as Aliyev's doing, who removed the "little prince," as he calls him, because he had become too powerful. But for the people in the region, this did not mean improvement. "Aliyev now has almost unlimited control over Azerbaijan's economy. He imprisons journalists, NGO staff, and professors, thereby crushing the last remnants of a functioning society," he says.

It fits this pattern that the government portrays the neighboring state of Armenia as an enemy, depicting it as dangerous and evil. "Azerbaijan needs this enemy image to justify the strict dictatorship to the population and to distract from domestic problems."

In my mountain hut, it's now two in the morning. I can't sleep: because of the altitude, every attempt to close my eyes ends with an adrenaline rush that immediately wakes me up again. I came to the area to photograph residents. My translator Rafael claimed that his car mechanic Tural knew someone here. But when we arrive, shortly before dark, we're not in a village but surrounded by abandoned houses.

Earlier in the afternoon, I had an uneasy feeling when Tural got into our off-road vehicle: tall, sunglasses, a Hugo Boss jacket stretching over his thick belly. With a flourish, he slaps two packs of cigarettes and a bottle of vodka onto the back seat. Soon he takes the wheel, drives off, and chats with Rafael in Azerbaijani. Apparently, he's asking questions about me; occasionally, he eyes me and says "Heil Hitler," "Ladies and Gentlemen," or "Let's go." Every few minutes, one of his two phones rings; he declines all calls. "He probably has two wives and keeps them secret from each other with separate phones," Rafael suspects.

I had found Rafael on the Couchsurfing website, where I was looking for a local translator. He was one of the few active users in the area. The 39-year-old, with curly black hair and a full beard, knows the Republic of Nakhchivan like the back of his hand. "You're lucky you found me," he wrote. "There are only a few here who truly understand what journalism means." When I tried to address the complex relationship between Armenia and Nakhchivan, Rafael replied: "We shouldn't write about such topics on WhatsApp. Let's discuss this in person when you're here."

I reached Nakhchivan airport at the end of March after a sixteen-hour journey via Istanbul. The entry went smoothly. My first impression: time seems to have stopped in the 1990s. Outside the door are off-road vehicles of the Russian brand Lada and men smoking and discussing. Shortly after, Rafael drives up. His outfit – sweatpants, fleece pullover, beanie – he will still be wearing in a week. Rafael is divorced and lives in his second marriage with Ella. In Azerbaijan, where divorces are frowned upon, this is quite unusual. The couple runs a small hostel and lives with their 9-year-old daughter in Rafael's parents' house.

During my two-week stay in Nakhchivan, I live in a cozy wooden cottage somewhat apart from the main house. When the food is ready, Rafael sends me a message on WhatsApp. The family's hospitality impresses me: although I don't speak Azerbaijani and only broken Russian, they accept me as if I were one of them. Once, Ella even prepares my favorite food: Pizza Margherita. During shared meals, Rafael takes on the role of host: he helps with cooking, serves the food, and makes everyone at the table laugh with his anecdotes. He does everything for his hostel guests. For our trips to the mountains, he specially acquired a robust off-road vehicle from Soviet times before my arrival.

I like Rafael very much. But there are also moments when I secretly curse him – for example now, where we're all drunk driving at what feels like 100 kilometers per hour (feels like, because the speedometer is broken and always shows only 20 kilometers per hour) over the bumpy country road. At the wheel is a whooping Tural, while a friend of his alternately hums oriental songs and shouts greetings to people by the roadside. My pulse shoots up, I keep nudging Rafael and beg him to make Tural slow down. "I have a family at home!" I call out.

But it doesn't help that Rafael admonishes Tural – seconds later, he overtakes vehicles again as if being pursued by the police. They then actually stop us shortly after. "People have complained about you," says the officer. It becomes dead silent in the vehicle. I hope in vain that our drunk driving will end here: Tural's friend gets out, exchanges a few words with the officer, and then gives the all-clear: "We continue driving, let's go!"

Yet in the afternoon, everything had been so peaceful. After about two hours of driving, we stop at a river where Tural's friend was waiting for us: Samir, a former police officer who has a vacation home here. We load chunks of meat, onions, bell peppers, and zucchini onto a wooden table and immediately begin chopping. No one speaks; everyone is focused on their tasks as if we were a group of old friends who regularly meet for barbecues.

In the background, a flock of sheep passes by. The sky is as gray as Samir's hair, but it's relatively warm. As the six shashlik skewers lie on the grill, Tural's large vodka bottle comes into play. I politely decline the first shot, but by the second, Rafael persuades me to drink along. "It would be impolite not to drink," he says, laughing as he pats me on the shoulder.

After a few glasses, the mood becomes exuberant. At some point, Samir strips down to his underwear and points toward the river. Tipsy, I follow him, also wearing only underwear, and call out to Rafael and Tural: "You too!" whereupon Tural is startled and shouts: "No YouTube, no YouTube!" This small misunderstanding stands symbolically for all of Nakhchivan: the people are friendly and warm-hearted, yet at the same time, you sense a constant fear – but of what exactly?

On the evening of my arrival in Nakhchivan, the rain beats incessantly against the windows of Rafael's car. We are on our way back from a tour of the capital. The outside world passes by the foggy glass only as silhouettes. Carefully, Rafael steers the car over the wet streets. "The people in Nakhchivan are isolated in their minds," he says, slamming his hands on the steering wheel. "They don't understand the basics of a free world. When I guide guests from my hostel through the villages, the locals ask: 'What do these foreigners want here? Why do they come to Nakhchivan? There's nothing worth seeing here; they must be spies!' They don't comprehend that tourists find Nakhchivan fascinating."

For Rafael, this is a direct consequence of Talibov's years of rule and the population's lack of education. "Ella and I read many books, but there's hardly anyone with whom we can share our knowledge." Rafael only returned to Nakhchivan shortly after Talibov was removed from power, about two years ago. "In the past, you couldn't have come here as a tourist. Opening a hostel would have been unthinkable," he says. Today, he can live here without having problems with the authorities.

Nevertheless, Ella and he are considering moving abroad. "Nobody knows how the political situation will develop. I wish for a better future and education for my children. And I want to discover the world. Simply lead a normal life."

More than a dozen pairs of shoes stand in front of the hostel entrance. It's the first day of Nawruz, the region's most important festival, symbolizing the beginning of spring and the triumph of light over darkness. The celebration lasts a week. Rafael's brother and sister are visiting with their families; the festively set table in the living room overflows with Easter grass and sweets. Next door, Rafael's children immerse themselves in a game of chess. From the kitchen comes the clinking of dishes while Ella, sitting on the floor, prepares dough pockets on a wooden board.

As the rain subsides, the family lights a large fire in the garden. Everyone jumps over the flames once, a ritual to drive away evil. The happiness of this evening almost makes me forget how serious Rafael and Ella's faces look in between.

A few days later. The sun is already approaching the horizon as Rafael and I arrive at the teacher's institute in Nakhchivan in the early evening, where future teachers for the entire region are trained. The school bell has just signaled the end of classes; students in white school uniforms stand in the schoolyard. We've come here because since my arrival, I've been wondering what moves young people here. Do they want to stay in this isolation – or do they dream of starting their lives elsewhere?

We get into conversation with 29-year-old Zohre, an acquaintance of Rafael's. She wears a bright orange shirt and pushes her bicycle alongside her. Zohre greets us with a smile, but when she speaks, her expression is serious. "I often feel restricted because I can't learn what I consider important," she says. "The education system is heavily regulated, which makes creative and independent teaching difficult." The university simply processes people through rather than being a real place of learning. The city itself also offers hardly any occupation for young people, causing many to fall into lethargy.

Anyone who can somehow afford it studies abroad. Zohre will soon leave Nakhchivan to study at Anadolu University in Eskişehir, Turkey. Her goal is a doctoral degree in Turkish language. Whether she will return afterward, she doesn't yet know.

"It depends on how life develops here. Nakhchivan is very isolated," she says. "What is completely normal in Europe is considered unusual, if not inappropriate, here." She points to her bicycle. People on the street would eye her mockingly and ask why she rides it; after all, she's not a child anymore. Zohre has had enough: "I want access to education, which is not possible here, and to lead a life without constantly being exposed to prejudice."

When we park the car in front of a gray prefabricated building half an hour later, the sun is almost disappearing behind the horizon. From his room window on the top floor, 20-year-old Fakhreddin waves to us. In his apartment, his mother immediately starts talking to me in Azerbaijani, which makes Rafael laugh. He says: "She wants you to tell her son to finally cut his hair."

In the living room are three large sofas, and carpets lie everywhere. Fakhreddin's mother and grandmother urge us to try the nuts and homemade cookies that are typically available during the Nawruz festival. "They want to get rid of their huge supply," says Rafael and laughs.

Fakhreddin wears sweatpants and a T-shirt; his slightly longer hair is neatly combed back. "Actually, I wanted to become a violinist," he says, "but my grandmother urged me to study economics to get a secure diploma and a government job. That was painful."

During the conversation, his mother interrupts him repeatedly. "I've always given my son everything. And now he wears such hair," she says, throwing her hands in the air.

Fakhreddin is the only man in the house. His father, once a police officer, died years ago in a traffic accident. This is also why his mother and grandmother constantly monitor him and worry about him: Where he is so late, why he sleeps so little, why he suddenly sleeps so much... But despite the family pressure, he remains true to his passion for music, plays violin, and writes rap songs about love. He says: "I will continue to fight and let my hair grow."

Soon he will complete his studies, and he plans to continue studying in Turkey afterward. His future is still open, as is the question of when he will serve his one-year military service, which he can postpone as long as he is abroad. When I address the politics in Nakhchivan, he only replies: "Not your business!" and breaks into roaring laughter along with Rafael.

In the mountain hut, the music has now fallen silent. My phone shows 5:14 a.m. Outside, dawn is breaking; light timidly penetrates my room. I have indeed slept for a few hours. Although I feel shattered, I am immediately wide awake.

I jump out of bed and hurry down the creaking stairs with my sock-gloves. In the living room, you can only hear the different snoring sounds of my three companions. The fire in the stove has just gone out; it's still pleasantly warm. Like a street dog in winter, I lie down on the floor and close my eyes again. But the euphoria of having survived the night keeps me awake.

I step through the door of the hut into the cool morning air and eat a piece of Swiss chocolate that I brought along. In the distance, Mount Ilandagh is illuminated by the first rays of the sun; behind it flicker the lights of the Iranian city of Jolfa. What a beautiful and strange piece of land Nakhchivan is, I think: it seems infinitely free to me and claustrophobic at the same time