Kazakhstan Time Travel

Just a few months before Covid-19 ushered in a wave of quarantines and travel restrictions, I set-off on a three week cross-country railway journey through Kazakhstan. In various compartments, I met people travelling for work, for weddings, and funerals. I saw children playing football in the corridors, and documented the lively conversations with strangers I met along the way.

Map of Journey: 16 Days - 225 Hours - 7500 Kilometers

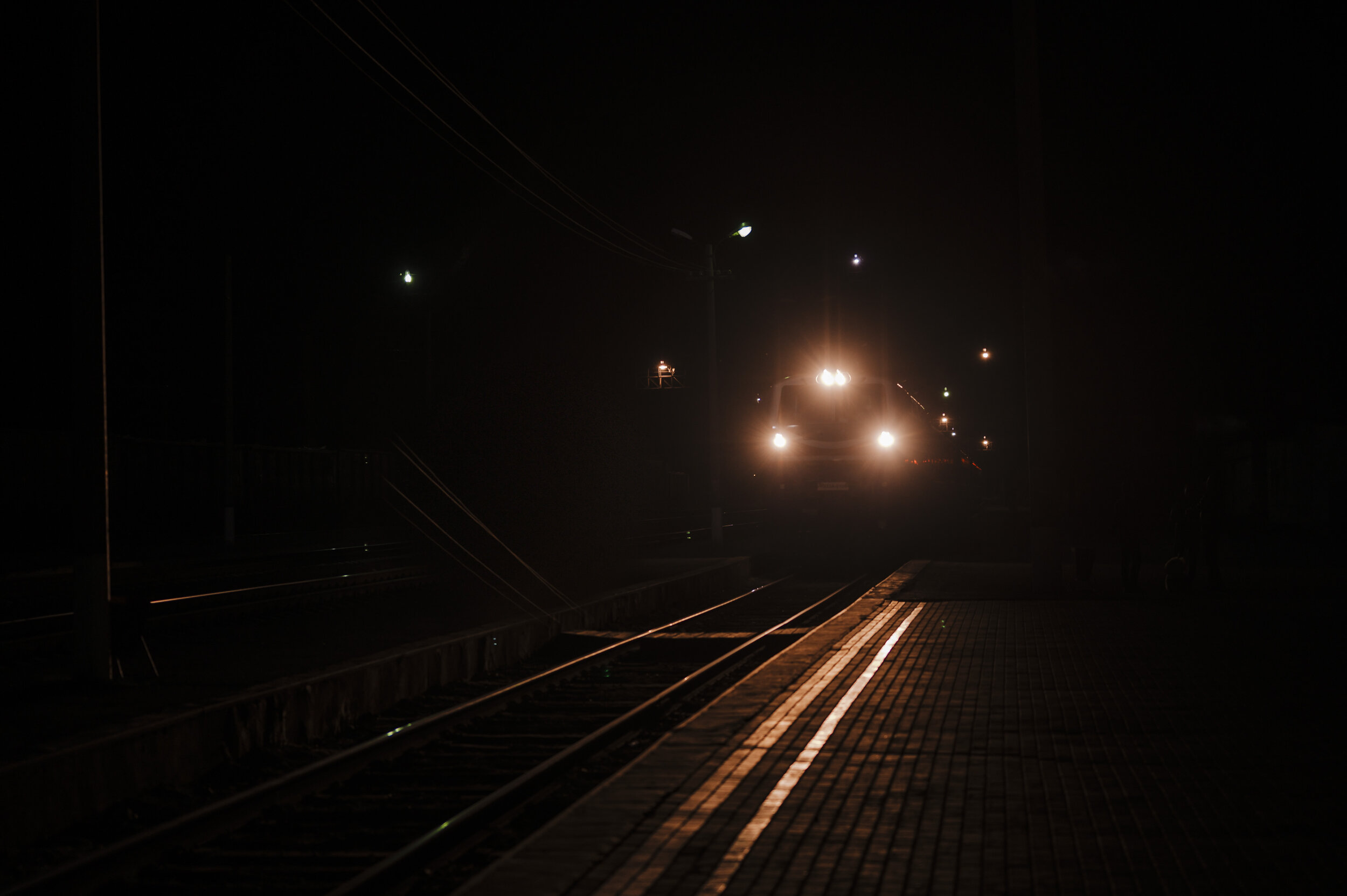

The monotonous rattling of the train travelling straight ahead accompanies us through the steppe of Central Asia. The air that travels with us smells of cooked food and the exhalations of dozens of passengers. Sounds drift over to me from various corners of the wagon: A sawing snore, children's screams, folk music and a hyperactive radio voice, just across from my neighbour. Lying in my upper bunk bed, I seek body contact with the cooling plastic wall because of the summer heat. I am in a twilight state between shallow sleep and nervous glances at my mobile phone: still no reception. I am trapped in the here and now. It is shortly after three in the morning. A few lights glide past the window, otherwise, it is pitch dark. It is the beginning of my almost three-week train journey across the endless expanses of Kazakhstan.

The train stations in Kazakhstan could also be called museums of the Soviet Union. Paintings or busts from that time often adorn the sometimes magnificent waiting halls.

Dina (79)

«Certainly I have spent several years in Kazakh trains and made hundreds of acquaintances during my journeys. Now I am almost 80 years old. Although there are now affordable plane tickets, I prefer to travel by train. The time seems to stand still here. At my age, there is no hurry anymore and I fully enjoy such train rides. »

Shortly before midnight, I board the night train in the former capital Almaty. At my side is Daulet as a translator for this expedition. The 26-year-old, well-fed Kazakh works for the country's Geographical Society. I met him on Facebook only a few days ago. His sedate, almost phlegmatic manner has sedated me since our first meeting and gives me a sense of calm. Daulet's response to suggestions of all kinds: "Yes, why not? That's how we do it." Now he lies in his blue work jumper in the bunk bed across from me, snoring to himself. Outside, a whistle sounds, newly arrived passengers prepare their night's lodging, and the train starts up again. We fall back into our monotonous rhythm. Gradually, sleep overcomes me, despite all the unfamiliar sensory stimuli.

A few weeks before, I was looking at a map of Kazakhstan and wondering how to get around in such a vast country. I soon found out that the state railway company is the country's largest employer, with 146 000 employees. Nevertheless, the railway network is only 16 000 kilometres long - far less than in Germany, although the area of Kazakhstan is the same as Central Europe.

The majority of the country consists of vast plains, sometimes merging into hills, and almost half is covered by sand or gravel deserts. The only mountainous area is in the south-east, where the Tian Shan mountain range runs along the border with China and Kyrgyzstan. The snow leopard, Kazakhstan's national animal, lives in the spruce forests. Among the country's 48,000 lakes is the Aral Sea, which has almost dried up. It represents one of the greatest environmental catastrophes of the last decades, caused by the large-scale cotton cultivation during the Soviet era.

In the small compartments called „Kupe“, four complete strangers are brought together in the smallest space on each journey. Sometimes lively conversations arise, but often the people also sleep or watch a movie on their mobile phones.

In Kazakh on-board restaurants the atmosphere is always exuberant. The wagon is filled with laughter and the smell of borscht. The waitresses bring one bottle of vodka after the other to the mostly exclusively male guests.

Marat

«For thirty years, the moving trains have been my second home. Area- dy my grandmother worked as a train conductor. As a child I often accompanied her with shining eyes. My job goes far beyond ticket control. Sometimes I feel like a psychologist. Over many years I have observed all differend kinds of people. Some seem happy, others

sad. Sometimes I give people advice, sometimes I laugh with them, sometimes I just listen and keep quiet. In any case, a benevolent being is the prerequisite for this profession. Often I think that nothing can make me astonished anymore and then something completely surpri- sing happens again. Be it an old man who fell out of his bunk bed and had to have his broken hand bandaged, or a woman who gave birth

to her child in a train. Soon I will retire. My seven daughters are already married and have children of their own. I don‘t think I will get bored. And if I do, I‘ll just start gardening!»

Aliya (20)

«This train is now only a few stops from its destination. Most of the time the train runs on time, but every now and then it makes extraordinary stops, for example when people don‘t live near a stati- on. It‘s the same in real life: you should always be ready to stop at the right time, even if it seems an unusual halt. There‘s never a direct route to your destination without stopping in between, just as a train never goes straight to the terminal.»

Often whole families travel with their children. Some of them even play football in the corridor of the waggons, others just discover and touch everything possible.

More than half of all inhabitants in Kazakhstan are under 29 years old. A high appreciation of family values still makes the older voices sound the loudest, which inevitably leads to an old-fashioned and entrenched social structure. Nevertheless, young people believe in themselves and that the future belongs to them.

The long distance trains usually run once daily in both directions. Since they are underway so many hours per route, one have to get up early in some areas to catch the train.

The many stops of the long-distance trains always entice with a wide range of small grocery stores or even whole snack stands. Food is on sale here until late into the night.

Most long-distance journeys begin and end in the former capital Almaty. Late in the evening, the station is usually very busy. Passengers say goodbye to each other, haggle with the train staff about the maximum amount of luggage and settle into the carriages for the first night.

In Kazakhstan there are three main reasons why people travel: Work, weddings and funerals.

The morning after waking up, the borrowed bedding is neatly folded and handed over to the train crew. This is a kind of ritual to pay respect to their work.

Alexander (20)

«People here say: It is important to have a warm heart and still keep a cool head. These words have often come to my mind since I started my training as a rescue worker. At first my parents were worried that

I was risking my life every day, but when they realized how hard I was training for it and how much I believed in this path, they realized the importance of this profession. However, even an experienced and qualified rescue worker may not be able to cope with a situation men- tally. My biggest concern is not being able to save someone in need - fortunately, this has never happened yet. Now I go to my parents, who live four hours away from Nur-Sultan. I enjoy the train rides, because you can always meet new people and think about your life.»

Among the country‘s 48,000 or so lakes is the Aral Sea, which is now almost dried up. It represents one of the greatest environmental disasters of recent deca- des, caused by the large-scale cultivation of cotton during the Soviet era.

Reyma (82)

«Until eleven years ago, we spent our entire lives in Af- ghanistan. We were among the children of parents who were a thorn in the side of the Soviet state at the time. People like us were dispossessed and sent to prison camps. Our parents wanted to avoid this at all costs, so they fled with us children to Afghanistan. Even today, Kazakh society in Afghanistan still includes several thousand people as an isolated community. When I came back to Kazakhstan, I had mixed feelings. Relief, joy and sadness were very close together. Now I was finally at home - but I had to leave all my friends and neighbours behind. In the end it was still the right deci- sion, because here in Kazakhstan there is peace and quiet, the only thing I still need at this age. Being on the rails is the most exciting adventure for me. You can drink tea all day long, meet new people and watch the steppe from the train window. It illuminates my inner self. »

It takes a long time to become a locomotive driver in Kazakhstan: Usually you start as an assistant and then drive a freight train for several years. Only then are you allowed to drive a passenger train. The locomotives in Kazakhstan come not only from the former Soviet Union, but also from the United States.

Although the old locomotives and wagons still make up the majority of the Kazakh railway fleet, there are now alternatives for routes between major cities: since 2017 a number of Talgo trains have been running in international passenger service, which are being assembled in Kazakhstan.

Kamilla (19)

«In Kazakhstan, it does not makes sense to follow politics. Everything is ruled by one man. Therefore, I am concentrating myself fully on my computer science study in Nur-Sultan. This is the future of humanity. Still, I am very priviliged to be able to study in a good university. Compared to young people in Europe, we are maybe much less educated in average, but we are much more attached to our family and way more patriotic. I live in a typical Kazakh family: My parrents think everything is good and we have to thank god for the great politicians and I often find myself debating with them. »

The police checks with sniffer dogs on trains on a regular basis, especially in areas with high crime rates.

he climate in Kazakhstan changes tremendously depending on the region: While in the south, it can be quite warm in autumn, around Nur-Sultan it can also be very cold.

Adylet (83)

«Anyone who still mourns the Soviet Union today is a complete idiot! At that time there was no freedom whatsoever, society was godless and lived under con- stant brainwashing. When the Soviet Union slowly fell apart, our family mostly ate only bread. We only survi- ved because our ancestors had a farm which they built up under years of hard work! Today‘s Kazakhs have all the possibilities, but all they do

is complain. It seems that the virtue of hard work has been forgotten. Today‘s politics are not perfect either, and the retired President Nur- sultan Nazarbayev still promises, as he did 25 years ago, that the best times are yet to come, but at least there is peace, open borders and enough food.»